CNN World is reporting of the non invasive x-ray analysis of the Mona Lisa and how Da Vinci was a master at using ultra thin layers of paint. The technique is called sfumato at Da Vinci of course was a master in applying.

CNN reports (the article is short so I will post in its entirety)

(CNN) -- Scientists have unlocked another Mona Lisa mystery by determining how Leonardo Da Vinci painted her near faultless skin tones.

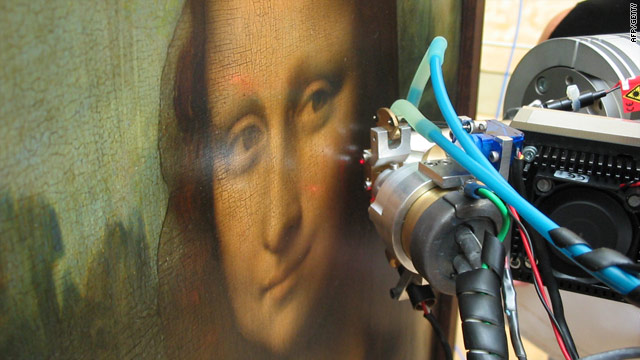

Using X-ray techniques, a team "unpeeled" the layers of the famous painting to see how the Italian master achieved his barely perceptible graduation of tones from light to dark.

The technique used by Da Vinci and some other Renaissance painters to achieve this subtlety is called "sfumato," and unraveling it allowed the scientists to determined the composition and the thickness of the paint layers.

Philippe Walter, a senior scientist at the Paris-based Laboratoire du Centre de Recherche et de Restauration des Musees de France, told CNN: "This will help us to understand how Da Vinci made his materials... the amount of oil that was mixed with pigments, the nature of the organic materials, it will help art historians."

Walter and his colleagues used X-ray fluorescence (XRF) spectrometry to determine the composition and thickness of each painted layer of the Mona Lisa in the Louvre Museum in Paris, where the painting is normally kept behind bulletproof glass. Art historians believe it was painted by Da Vinci in 1503.

They found that some layers were as thin as one or two micrometers and that these layers increased in thickness to 30 to 40 micrometers in darker parts of the painting. A micrometer is one thousandth of one millimeter.

They believe this characterizes a technique of painting that uses a glaze, or very thin layer, to build up shadows in the face.

The manner in which Da Vinci painted flesh, "his softened transitions," were pioneering work in Italy at the end of the 15th century, say the researchers, and were linked to his creativity and his research to obtain new paint formulations.

Walter said it is almost impossible to see any brushstrokes on the Mona Lisa.

The research, which is reported in the journal Angewandte Chemie, also looked at several other Da Vinci paintings and could eventually help to determine when and how he painted some of his masterpieces.

However, Walter, added: "There is still plenty of mystery surrounding the Mona Lisa. This does not tell us why he painted, about his motivation, just about the materials."

Carol Vogel also wrote an article on the analysis of art by Matisse

To read the full article, click HERE.Before they turned to high-tech analysis, the conservators removed the varnish and previous restorations from “Bathers.” As a result, the colors came through more brightly. (They ended up removing the varnish from 20 of the 40 paintings in the show.)

In addition to their work with the paintings, the curators unraveled the steps that had gone into the making of a suite of four large-scale relief sculptures depicting the back of a woman inspired in part by “Three Bathers,” a Cezanne painting owned by Matisse. The sculptures, which he began around the time he was working on “Bathers” and developed over 23 years, also grew more and more radical over time.

Using laser scanning, they better understood how the process that went into the sculptures’ evolution. The first, depicting a female body, was made in clay and then he cut two casts in plaster, one to make in bronze, the other to use as a starting point for the next sculpture. The scanning showed how he used a cast from the previous sculpture for each of the four works, changing the surface of each succeeding figure until the overall form had a flatter surface and was quite stark and architectural. “Like ‘Bathers,’ it’s one conception being evolved over all these years,” Elderfield said.

The curators trace how Matisse added or subtracted details, scraped and rescraped the surface, moved objects, sharpened lines – and juggled several works, borrowing from one, experimenting with another. The result is a complete portrait of the artist during one of the least understood, yet critical, periods in his life.

No comments:

Post a Comment