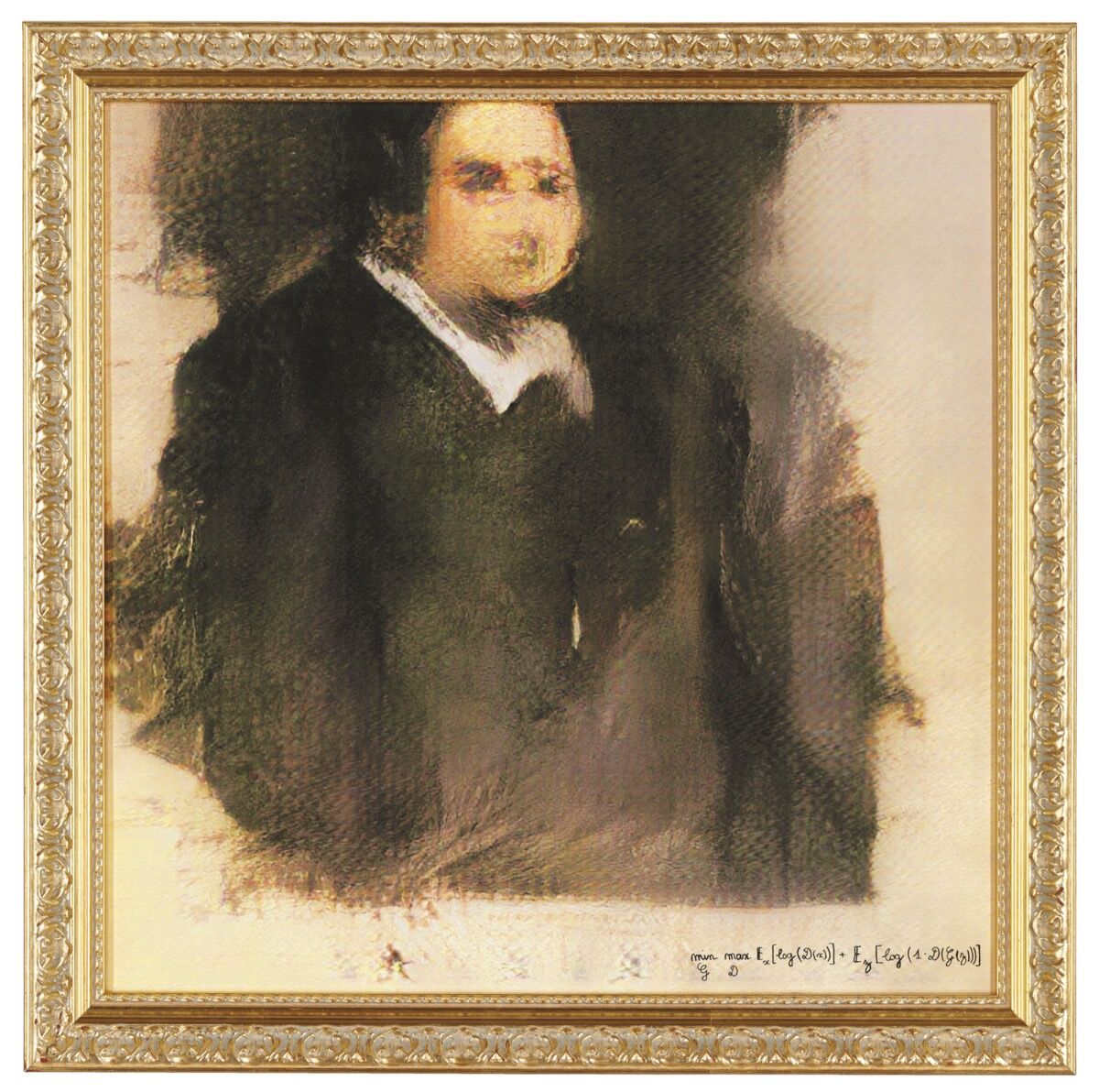

Last week I posted about an upcoming sale at Christie's of an artificial intelligence portrait being offered with an estimate of $7,000-$10,000 (click HERE to read that post). The computer generated portrait was based upon thousands of input images of portraits between the 14th and 20th centuries with an algorithm then developing the new AI created work.

The painting did sell, $432,500 after the buyer's premium. Artsy ran a good story on the sale of the painting and AI artwork.

Artsy reports

Source: ArtsyOn Thursday, in the same auction in which an Andy Warhol print sold for $75,000 and a work by Roy Lichtenstein sold for $87,500, a computer-generated artwork grabbed $350,000 ($432,500 after buyer’s premium). The work, titled Edmond de Belamy, from La Famille de Belamy (2018), was initially estimated by Christie’s for just $7,000 to $10,000.

The portrait was produced using artificial intelligence by Obvious, a Paris-based collective. Thursday’s price is, of course, out of proportion to any AI artwork ever sold; in the past, figures have typically been in the $10,000 to $20,000 range. The six-figure price is even more surprising, given that no AI artworks have been exhibited by any top galleries in New York or London before.

So how can an artwork from a little-known group bypass the primary art market and go directly to Christie’s, and then grab a shocking price? This off-the-chart price comes as a result of a two-month media circus ahead of the auction, which started with a well-crafted article in Christie’s online magazine. The news then ricocheted around the media, with lots of unfounded claims, such as “the first portrait being generated by AI” to “the first AI art to be sold at auction” to “the art made is by the machine with no human artist.”

These claims were refuted by Hugo Caselles-Dupré, one of the three makers of the work. In an interview with Jason Bailey at Artnome, he said: “I’ve got to be honest with you, we have totally lost control of how the press talks about us. We are in the middle of a storm and lots of false information is released with our name on it. In fact, we are really depressed about it.”

AI art history

Artists have been using AI to create art for the last 50 years. The most prominent early example of this is the work of Harold Cohen and his art-making program, AARON. American artist Lillian Schwartz, a pioneer in using computer graphics in art, also experimented with AI.

The Christie’s work, however, is a part of a new wave of AI art that has appeared in the last couple of years. Traditionally, artists using computers to generate art had to write detailed code that specifies the rules for the desired aesthetics. In contrast, what characterizes this new wave is that the algorithms are set up by the artists to “learn” the aesthetics by looking at many images using machine-learning technology. The algorithm then generates new images that follow the aesthetics it had learned. The most widely used tool for this is Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), introduced by Ian Goodfellow in 2014, which have been very successful in many applications in the AI community.

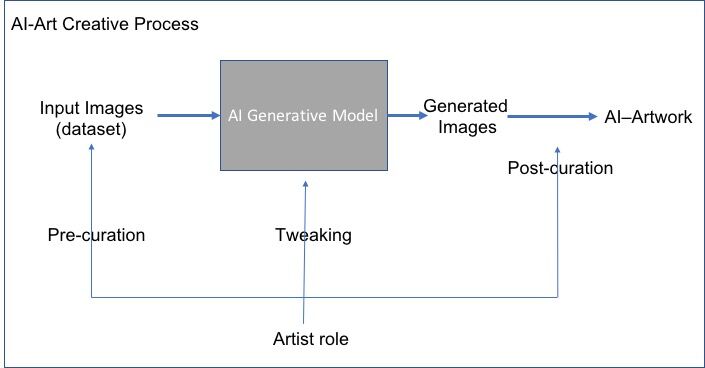

The claim that the art is made by a machine, without a human artist, is, of course, not true. The creative process heavily involves the artist. The artist chooses a collection of images to feed the algorithm (pre-curation); in the case of Edmond de Belamy, this was a set of traditional art portraits. These images are fed to a generative AI algorithm that tries to imitate these inputs. Finally, the artist heavily sifts through many output images to curate a final collection (post-curation). Basically, the algorithm fails in making correct imitations of the pre-curated input, and instead generates distorted images that surprise us. If the algorithm would succeed in imitating the input data, it would not be even be interesting as art. Several artists have been exploring this process in the last three years, such as Tom White, Mario Klingemann, Anna Ridler, Robbie Barrat, and others.

Understanding what AI art means

Understanding this process is crucial in characterizing what AI art really is. If we look at the creative process overall, not just the resulting images, AI art falls cleanly into the category of Conceptual art. The art is not just in the outcome, the art is in the process that leads to that, including the curated dataset, the choice of the algorithm and its parameters, and the post-curation.

The auction raises unprecedented ethical questions about the attribution of AI art. In the weeks leading to the auction, the Edmond de Belamy portrait has received heavy criticism by the AI-art community for being derivative and not original. AI artist Robbie Barrat also said that the code and the dataset used to produce the work is written by him.

In fact, in a documented exchange on the code repository site Github from October 2017, between Barrat and Caselles-Dupré from Obvious (using the alias “Caselles”), Obvious asked Barrat for the code and even repeatedly pushed him to change the code for them. Indeed, Obvious said that they used the code by Barrat and modified it. “If you’re just talking about the code, then there is not a big percentage that has been modified,” said Caselles-Dupré in an interview with the Verge.

Looking at AI art as process-driven Conceptual art is crucial in resolving the attribution and originality issue. The art is not in the outcome or final image, the art is in the process, as a form of Conceptual art. If you copy the process (the input data and the tool used, in this case), then to what extent can you claim the outcome to be original? If you take one of Sol LeWitt’s wall painting instructions, and install it yourself, can you claim that the art is yours? I doubt anybody in the art world would accept that. Yet this is exactly what is happening here. If you take the code and the same input dataset and press the button to repeat the process, can you claim the outcome is your art?

The future of the AI art market

Barrat, when asked about the sale, said his main hope is that “the high price will set a good precedent for other AI art being sold in the future, and that despite the portrait Christie’s chose to auction being very shallow, people will see it and attention will be drawn to actual legitimate artists working with AI—like Mario Klingemann, Helena Sarin, Tom White, to name a few.”

Indeed, I believe this is the hope of the entire AI artist community.

Apart from some of the works by early pioneers like Harold Cohen, AI art has historically not been warmly welcomed by galleries. Until recently, it was almost nonexistent in the primary art market. That may be starting to change. Recently, Nature Morte gallery in New Delhi held an exhibition of AI art entitled “Gradient Descent,” which featured work by Anna Ridler, Mario Klingemann, Tom White, Harshit Agrawal, Jake Elwes, Memo Akten, and Nao Tokui. At the SCOPE Miami Beach art fair in December, AICAN art—AI art originally produced by the Art & AI Lab at Rutgers—will be exhibited with no human artist’s name attached. Now that Christie’s has given its imprimatur, will the primary art market be ready to embrace and exhibit the new wave of AI art?

Despite some signs of warming, actual AI sales in the art market have been limited to date. In San Francisco in 2016, 29 artworks by a machine intelligence team at Google were sold in an auction for a total of $98,000, with Turkish artist Memo Akten’s work grabbing the highest price of $8,000. In 2017, AICAN art was sold for $16,000 in a benefit auction in New York. The Nature Morte exhibition in New Delhi displayed the art with price tags ranging from $500 to $40,000.

Now, with an AI a piece sold for $350,000, all bets are off. Who bought it? Why? Do they want another one? Will the publicity from this sale bring more attention to the artists already working in this field? Or will the unsolved issues of attribution and copyrights hunt the field and scare buyers away? Will that high price encourage small galleries to embrace AI art to the point that it becomes a trend, only to die away fast? It is always dangerous for an artist—or art form—to have such a huge spike in price, specially it happened in the secondary market before it even hits the primary market. It remains unpredictable, therefore, how Belamy’s triumph at Christie’s will ultimately swing the AI art market.

No comments:

Post a Comment